What is software development? At a most basic level, it is the activity of using a programming language to achieve some set of goals over time. It includes everything from scripts that a graduate student might write to analyze some data to massive systems that control aircraft. As our world continues to progress technically, software development will likely become even more commonplace than it is now. In this post, I aim to provide a comprehensive overview of how one can develop software efficiently using free and open source tools on Linux.

With the rise of software development has come the discipline of software engineering. Software engineering is the study, generalization, and application of the practice of software development. It often concerns it self with how to most efficiently use time and developer resources to achieve the goals of a particular project. Within software engineering are methodologies which provide templates that have been shown to consistently produce results.

Software engineering methodologies (Waterfall, Agile, Kanban, etc…) differ over the exact components and ordering of the processes, but there are some overarching themes that are consistent. They begin by engaging stakeholders to gather precise, accurate, and prioritized requirements. Then these requirements are synthesized into a design which is evaluated and refined through communication with stakeholders. As the design becomes clearer, engineers begin to develop individual components that represent high value returns to the stakeholders. As components become available, their designs are tested individually and as part of the integrated whole. Finally, once the design is considered finished, it is released to the world.

However if all we study is software engineering, we perhaps have missed the point. We lose sight of the development of the individual over time, their maturation in the discipline, and their self awareness of their abilities. This is what I call software craftsmanship.

Software craftsmanship highlights the need for the development of the individual developer over time. As I use it, software craftsmanship is the inherently personal processes of software engineering that transcend a project boundary. Software engineering more often focuses on a topic like task management as something that is shared among a team. Whereas, software craftsmanship is the self awareness of how an individual will progress through the task. Software engineering often looks at measures of performance across an organization. Whereas, software craftsmanship focuses inward as to how one can grow for the long term.

That is not to say that software craftsman are alone. A true craftsman seeks out mentor-ship and the experience of others as they grow in their trade, and joyfully shares their knowledge with others. Their passion for their craft excites and inspires others to go forth in their example. This post aims explain how I have learned the craft of software engineering using open source technologies.

This post is the second in a series focused on using Linux to get work done. The previous post serves as an introduction to Linux for general use. If you have never used Linux before, you should read that article first. While this article is primarily aimed at new developers, I hope that some of the insights that I offer here will empower more experienced developers to get more done as well.

How to read this post

There are three ways not to read this article:

First, do not try to read and apply this article all at once. Software development is a skill that requires practice; so I recommend practicing before making a decision on whether something is useful or not. Instead, first skim the entire article; then pick a section or subsection that you would like to focus on improving, read it carefully, and integrate it into your work-flow. Software development is a creative process, and like other creative processes different approaches will work better for some than others. That is not to say that there are not norms or best practices that on average show improvements, but how evidence-backed concepts are implemented will very from person to person.

The first time that I was aware of doing this with software development when reading Drew Neil’s excellent book “Practical Vim”. The book is a collection of more than 50 tips about how to use the Vim text editor. Yes, reading the book through passively was fascinating. It gave me several insights into the elegance of using Vim that stick with me to this day. However, when it really became powerful to me is when I applied what I was reading to the tasks that I had at work. When I put them into practice, I started to see other areas and applications where I could use my new found skill. Reading actively is essential.

Second, these practices are not dogma, you will not be excommunicated for following or not following them. From my experience, you it will not be too long before you will hear comments like these:

- If you are not using a

$TEXT_EDITOR, you are an inferior software developer. $LANGUAGE_1is always a better language than$LANGUAGE_2be cause it has$FEATURE$ENGINEERING_METHODOLOGY_1is strictly better than$ENGINEERING_METHODOLOGY_2, why are you stuck in the past?

Often upon further extermination, these kinds of claims can be shown to logically false and are more an expression of the ignorance or preference person who said them. That is not to say that they may not defect some truth, but software development is a study of trade-offs. Lets look at a some specific examples:

Vim is a better text editor than Nano

This is an incredibly vague claim. There are may ways in which text editors may be better than one another: simplicity of implementation, number of lines of efficient, correct code written per hour by an new or experienced user, flexibility to new programming languages, etc. And in some ways, yes Vim is better than Nano: it offers features such as build system integration, code completion, and code navigation that have been shown to increase productivity for the average developer. However, Vim has a steep learning curve requiring weeks to become proficient and Nano can be used by many users in a manner of minutes. Over time, it can be shown that Vim offers better productivity, but that doesn’t make it strictly better than Nano in all cases.

Java is a better language than C because it does not use pointers

This claim is also vague. But oftentimes when you push the people who make it, they mean that Java is better than C because it is garbage collected and is immune to some classes of memory related errors such as segmentation faults or use after free errors.

However in exchange for the immunity to segmentation faults or use after free errors, Java now has to preform garbage collection.

In a “real-time” context, your you need the code to have a precise, consistent runtime, garbage collection can be a huge source of variation.

This means that move from something that will be hard to get working to something that will likely never work.

Beyond that, a pedantic C developer might point out that Java has the concept of a NullPointerException which often operates similarly to a segmentation fault as far as program execution goes.

Ultimately, in both of these cases, you need to refine the question and determine objective means to come to a conclusion. Software engineering the is study of techniques that make software development more repeatable and effective. Software engineering gives us tools to answer questions such as: Do I favor performance over readability? Resilience over performance? Portability over Implement-ability? These are all choices that skilled software developers make and one a careful application of process can help answer.

Finally, these practices are best learned in community. Often when we are alone, we loose perspective that can be gained from others. That is not to say that internal reflection is not important, but that others can provide keen insight into ourselves that we might otherwise be unwilling or unable to see.

I can think of several more seasoned craftsman who have shaped my development practice: From one of my first technical mentors Irish who inspired me to get things right and to care about my tools. To Austin, one of the most gifted engineers that I know who taught me the importance of making a design that communicates. Marshall who showed me observant technical leadership and a quiet curiosity. My colleagues at Boeing who showed me what it means to fit into the bigger picture and make a difference for customers. My adviser Dr. Apon who showed me the power of empowering your team and taught me about the science of computing. Dr. Malloy who taught me to prototype early and don’t be afraid to fail. To Dr. McGregor who showed me the importance of history and trade-offs in design.

We learn best in community, be aware of who you can learn from and who you can best teach. We all have something to offer.

Gathering Good Requirements

What are requirements?

It may seem odd that I don’t begin with a discussion of languages and tools. Remember my discussions of trade-offs in the previous section? You can’t really begin to discuss the way you are going to implement a design until you truly understand the constraints involved. In most software engineering methodologies, this is called requirements analysis or requirements gathering.

So what does this do with the craftsmanship of software? Writing good requirements is difficult. Almost no one knows exactly what they want from the beginning and can correctly anticipate how that will shift over time. A software craftsman can tell the difference between certain and uncertain requirements and design in such a way as to obviate those concerns. However, a good software craftsman can also identify when the stakeholders are asking for something impossible balances of conflicting concerns. My graduate software engineering professor put it this way:

So what are requirements? Requirements are not just what the software is supposed to do (functional requirements), but also qualities of the system (non-functional requirements). Functional attributes are conceptually simpler. You can often perform a test, does it do what is required or not. This then implies the responsibility to actually test those requirements, but I will address testing later.

However non-functional requirements can be just as important if not more so. Non functional requirements are those requirements are attributes of the system. It’s hard for these requirements to run an explicit test. Example of non-functional requirements may be it must be maintainable or modifiable. For these kinds of requirements different kinds of processes are needed to access if you are actually meeting your requirements; I’ll discuss that in the section on verification.

The goal of considering requirements and stakeholders is to build realistic expectations for yourself and others. Seldom if ever are you going to write the next big application that is going to skyrocket to a million users. Rarely are things going to take the time or cost that you think they are going to, especially if you don’t think carefully about what is involved. Setting unrealistic expectations ruins credibility, destroys moral, and wastes time and effort. You are not going to do this perfectly; the goal is to do better than you would if you did not try.

What are good requirements?

A good requirement is: correct, unambiguous, complete, consistent, prioritized, verifiable, modifiable, traceable, necessary ~ John McGreggor

At first this list seems very obvious, but there is often more nuance to this, so lets break it down.

Correct means that the system does exactly what it is supposed to do. For example, people seldom need 100% accuracy, and can tolerate 99% accuracy if the system runs an order of magnitude faster. In economics, these trade offs are measured in marginal costs – how much would you give up for a small gain in something else. Now people may not know at first what they are willing to trade, but a good requirement seeks out how to measure the user’s marginal cost structure.

Unambiguous indicates that the requirement can be interpreted in only one way.

However, unambiguous requirements are really challenging to write.

For example, consider the requirement that a function return a python dict.

On one level the requirement is unambiguous – it names the specific type.

However, often what is actually required is a dict containing certain keys which in turn refer to values of a specific type.

Complete requirement describe the totality of the requirements. For example consider this definition of a find operation in a dictionary: it returns a exactly the value associated with a key. However, this leaves out a key part of the requirement, what should be done if the key cannot be found? This doesn’t mean that the behavior should always be strictly and formally dictated. A good example of this is undefined behavior in C/C++. Compilers rely on allowing certain outcomes to produce unknowable effects to optimize the generated code for heterogeneous hardware and simplify implementation. The point of having complete requirements is to specify what behaviors are well-defined and which are not; not to specify which behavior to take in every case.

Consistent means that it is possible that all requirements can be implemented at the same time. On one level, this means that functional requirements should be non-contradictory. On a deeper level it also means that non-functional requirements should be non-contradictory. For example, consider the requirement that a system be highly usable. This may be in conflict with requirements such as high security or extensive modify-ability which tend to increase complexity.

Few if any systems have ever implemented every feature considered. In this case, budget concerns (both cost and schedule) can limit the extent of the implementation of the system. Priorities are how we make these decisions. When considering priorities, it is key to consider the dependencies of a requirement and what would be lost if the feature is not delivered. It is also important to consider a project with multiple stakeholders is a form of multi-objective optimization. In this case, there may not be one globally optimal point, but several Pareto optimal points. Priorities need to reflect both kinds of concerns.

Verifiable means that it is possible to know if a requirement has been completed. For things like functional requirements, this can be easier since the system either does or doesn’t meet its requirements. This is not always true, consider massive computation problems. You may not be able to afford to run an experiment twice. In this case you need to develop proxy requirements that approximate your actual needs. For non-functional requirements, it can be essential to develop metrics that accurately reflect the extent to which the requirement is met. For example usability, usability could be assessed by having potential users use an application and track what they can do without help and how quickly they can do it.

Modifiable indicates that a requirement can be changed without necessitating making substantial changes to other requirements. That is not to say that lock in and hard requirements should be avoided in all circumstances. Rather, hard requirements and lock-in should be considered carefully. A more complete treatment of modifiable requirements has been written by Gregor Hohpe. A clear personal example of this is when a team that I was working with required support of a particular protocol. Requiring this protocol essentially limited their design space to one very expensive option because the protocol was proprietary to one vendor. Did they actually need this? Perhaps they did. In reality, they could have considered other and possibly better designs if they relaxed this requirement.

Trace-ability is not so much a question of the content of a requirement but rather the process that created it. The idea is that you should be able to give a rational basis for why the requirement was introduced in the first place. It can be “traced” to its cause. Trace-ability becomes increasingly important for long standing projects where the understanding design decisions of years past can become a act of archaeological excavation and avoid repeating the mistakes of the past.

Lastly the principle of necessity is the Occam’s Razor of software architecture. Systems that are less constrained are easier to build. I remember countless times where I later relaxed the original design constraints of my code after learning that I had made an unnecessary restriction.

Stakeholders: Who makes the decisions?

So who makes these requirements? That would be stakeholders; those who have an interest in the outcome. Often they are the persons funding the effort, will be using the results of the effort, but also those who will be leading the effort. At this point one may say, “but this is a personal project”, or “no one outside of my team will use or care about this” to argue that they don’t need to think about stakeholders. These views are misguided.

Even for personal projects you have yourself as a stakeholder. Both yourself now and in the future. You never know when you are going to need to understand, adapt, or reuse code that you are writing now. It is important to consider what you may need for this task in the next month, year, or decade.

Often the process of thinking about who the stakeholders are can be illuminating on just how your experiment, tool, or library will be used. You could discover that you may have other users in the future. You could uncover that other uses of your design. You might design things differently.

Different stakeholders have different priorities and requirements. Too many times, I have seen systems that were never designed for anyone else to use them. They were undocumented, untested, and in many cases had to be substantially rewritten. Get their feedback early and often.

- Who are the stakeholders and requirements for your system?

Crafting a Design: Converting Requirements to an Architecture

How do I get better at design? Study existing designs

One on level, this suggestion goes without saying. Of course, you should learn from the successes mistakes of others. The is true regardless of what field or task you are facing.

You may be tempted to think that you are the first person to face a particular challenge. This is likely not true. Maybe you have different tools to work with, maybe you even have some unique problem that truly prohibits the most common solution, but that doesn’t mean you are the first to face such a challenge. The “Teacher” or “Preacher” or Ecclesiastes said it best, “There is nothing new under the sun.” You may have to look to completely different disciplines than the ones you exercise regularly, but more than likely you are not alone.

I am constantly amazed how many “new” innovations are simply either better tooling or better marketing for a solution that was developed in the early days of UNIX. Take containers for example. These concepts were first introduced in FreeBSD as “jails”, and improved in Solaris as “crossbow”. Yes, docker provides a substantially better interface for building and distributing containers than these existing technologies, but that doesn’t mean it was first.

Now how can one learn the most from source code or architectures written by someone else? I suggest that you read with a purpose; I’ve recorded some thoughts on this in my post entitled “Learning to Learn: Reading” Here are some common questions that I ask when I am reading to understand a code base:

- What are the major parts of the code base/architecture related to what I do?

- Why did each one need to be included? Understanding the role a component fills can provide guidance about what kinds of roles or information you may need to implement your system.

- How are the major components named and why? Naming is powerful in that shapes the way that we think about the system. A good name maps uniquely and naturally to the purpose of the thing that is named.

- What interface or interfaces did they use? A good interface does not “leak” to reveal information about the information. Often you don’t have access to more than the interface of an object or function. Interfaces are the connective tissue of your application and how they are designed matters.

- How do they accomplish their task? Implementation details matter. Exactly how processing and memory resources are utilized matters. Sometimes you just need the structure of a solution.

- What impacts would alternative designs possibly have on the usage of the interface? Understanding the trade-offs that exist within an architecture will guide you to better weigh which trade-offs that you should make yourself.

- What could I reuse design ideas from this work? Legally (is it allowed by the license) then either actually (copy/paste/

#include/import), pragmatically (implement a analogous interface, or create an “wrapper”/“adapter”), abstractly (use the idea, but depart substantially from the interface)? Why or why not? Reusing work saves time and effort if possible. Keep in mind you don’t have to reuse the implementation to learn from it. - How does this design compare/contrast to other designs preforming similar tasks? Why might these changes exist? Before you make your own trade-off decisions, understanding how others have made them can help you make them yourself.

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of this design? Once you have considered all of the trade-offs, it’s time to make finally decide what is good and bad about a design.

The ordering here is important. First you need to understand what a design is on its own before you can consider using it, then comparing it, and finally evaluating it.

In the remainder of this section, I want to highlight a series of books, software, and other resources that have shaped my thoughts on software design.

- “Object Oriented Design Patterns” by Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, Ralph Johnson, John Vlissides. This book while also about specific patterns on how to construct software, really introduced me to the concept of how to consider a broader class patterns than simply function prototypes.

- “Modern C++ Design: Generic Programming and Design Patterns Applied” by Alexander Alexandrescu. This book is dense and introduces the concepts of using generic and meta programming to implement common software patterns to build higher levels of abstraction.

- “Functional Design Patterns in F#” by Scott Wlashchin. This talk introduced me the concept that design patterns could be implemented in abstract ways to solve the same problems.

- Linux Kernel. The Linux kernel showed me how much could truly be done with a comparatively simple language like C.

- Clang/LLVM. LLVM has a host of advanced programming methods and structures used throughout its design. It is a veritable menagerie of cool data structures and algorithms.

I’d also like to caution against using Stack Overflow, random GitHub repos, and other Internet sources unquestioningly. The quality of information you get depends greatly on how carefully it was constructed. While there is doubtlessly many examples of good design and best practices, there are [countless studies that record poor quality answers](https://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=stack overflow quality) on platforms such as these.

What Lessons Have I Learned?

Software craftsmanship is not learned overnight. It isn’t even necessarily learned reading posts or books such as these. It is learned by doing and by learning from the doing of others. In this section, I want to highlight some of the most important lessons that I have learned about software engineering.

Quality Attributes: A powerful way to think about non-functional requirements

One final tool that I think has been very powerful in how I think about software craftsmanship is quality attributes. Quality attributes are a way to think about non-functional requirements of a system. Here is a listing of Quality Attributes that I learned about in my graduate software engineering course:

- Efficiency

- Time Economy - does it run quickly? Can we implement it quickly?

- Resource Economy - does it efficiently use hardware/human resources?

- Functionality

- Completeness - does it do everything that we want it to?

- Correctness - does it handle everything that it does handle correctly?

- Security - how robust is the security model, and how resilient to the modeled attacks it the system? Do we care?

- Compatibility - does it fit into our existing work-flow?

- Interoperability - does it inter-operate with our our other systems?

- Maintainability

- Correct-ability - how easy is it to fix bugs when they occur?

- Analyze-ability - how easy is it to figure out what is going on with the system?

- Modify-ability - how easy is it to modify the functionality of the system?

- Test-ability - how easy is it to test that the system is operating as expected?

- Portability

- Hardware Independence - can the system run on multiple kinds of hardware?

- Software Independence - can we change the underlying software dependencies (the operating system, standard library, other library components, etc…)

- Adaptability - how can the system adapt to new circumstances without being modified?

- Install-ability - how easy is it to install on the target platforms?

- Co-existence - can the system be installed or used where other systems are installed or used?

- Replace-ability - how difficult is it to repair the system after it has been installed?

- Reliability

- Maturity - how much testing and use has this system had before it was deployed?

- Fault Tolerance - how many and which kinds of faults can the system experience before it stops offering meaningful service?

- Recover-ability - how quickly do we recover from a fault after it has occurred? What do we have to do in order to recover?

- Usability

- Understand-ability - how easy is it to reason about the system to new users and developers?

- Learn-ability - how quickly can users learn the new system given their current knowledge?

- Operate-ability - how quickly or easily can users operate the system?

The important thing to recognize about quality attributes is that they represent trade-offs. To make something more secure, you often make it less usable and adaptable. To make something more adaptable or modifiable, you often make it less understandable. So when thinking about quality attributes in a design, it is important to think about which attributes are most important, and what is the lowest and highest level of each that is required.

So how can one design for quality attributes, let’s consider a few examples:

- Design for “native paradigms” – this requirement emphasizes the learn ability of the system for developers. By using software patterns that they are used to, they will likely be able to learn and modify the system more easily. However, using native paradigms make the system less portable to systems that don’t share these paradigms. I tend favor native paradigms things that are unlikely to change. You probably won’t rewrite the entire application in a different language, so using a language paradigm is probably ok. You probably will change the database system or UI, so organizing your data to optimize for a particular database/graphical toolkit probably isn’t worth it.

- Favor small modules and functions with a single task – this requirement favors modify-ability and understand-ability of individual component over the time/resource economy of the whole system. From personal experience, the cost in time/resource economy is overstated; optimizing compilers can often remove the layers of abstraction introduced completely, and the improved readability of the system is very often worth it. Additionally, when you isolate concerns like computation from IO, you have to change less if you want to introduce different IO or computational patterns later.

- Prefer self-describing IO formats (protocol buffers, HDF5, JSON, CSV, ORMs). Using these formats makes your system more inter-operable, but will likely increase your resource usage over a custom wire/disk protocol. Personally, I tend to prefer Interoperability and switch to a custom protocol later if I have to for resource constraints.

Diagramming: A Quick Picture is Worth a Hundred Hours

One of the best examples of lessons that I didn’t learn by reading, but by doing is the importance of prototyping and diagramming. In every software engineering class that I have ever taken, you would hear about something called the verification and validation curve as a model of the process for design software. You can see an example of it below:

Tasks at the top of the V have high impact, and tasks at the bottom have less impact on the final design. However there are a two major problems: At the beginning of the V, you have very little information about the design and what impact particular design decisions may have. At the end of the V, you have a lot of information about the impact of design decisions, but less ability to change them without massive cost. Therefore, it is desirable to be able to get as much information as possible to make the right decisions earlier in the process. This is where diagramming and prototyping can be enormously helpful.

Diagramming makes a pictorial representation of one or more aspects of a system and possibly how they interact. The major benefit of a good diagram is that it can take fraction of the time to create a diagram useful diagram than it would take to implement the system and has the side benefit of often more understandable to clients and colleagues. I have found that I can create diagrams for a half dozen different candidate designs in the time it would take to code one component of a larger system.

A good diagram often doesn’t display every aspect of the system. Rather it highlights whatever aspect of the system that is currently important to the viewer. If you need to consider a different aspect of the system, make another diagram. It won’t take you too long.

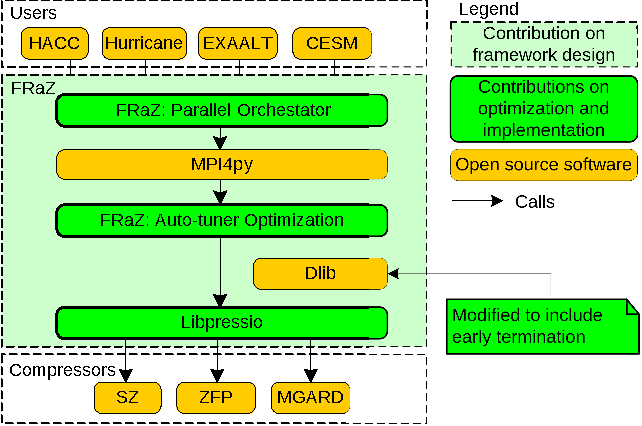

Here is an example from a paper that I published for FRaZ – a compressor framework that I developed while at Argonne National Laboratory:

Does this diagram show everything we did in the system? No. This diagram was intended to show the major elements of the system, how they interact, and which elements we wrote vs got from others. Now this is a publication quality figure, like what one might put in a presentation or a paper, but not all diagrams need to be this refined. The original version of this diagram was just a sketch on a sheet of paper that took me about 10 minutes to make. The publication quality version took about an hour, but the whole system took me weeks if not months to write.

Now, what and how can I diagram software systems? You could potentially diagram any aspect of a system where you want to consider multiple possible implementations. A book that I found helpful on subject is “UML Distilled” by Martin Fowler. Two notations that I have found helpful are UML and AADL. UML (unified markup language) is a notation that provides a common design language for expressing system interactions. A vast majority of the time I use a subset of UML. Another notation that I have used is AADL (architecture analysis and design language). I think it does a better job of modeling information flow than UML by forcing you to focus on inputs, outputs, and their formats. I don’t use these notations strictly, but where I think they are helpful.

Lastly, what tools should I use to create diagrams? Most of the time, I use a white board or pen and paper. The goal is to reduce the effort of brainstorming interactions. However, when I need something that looks more “professional”, I use either Inkscape, draw.io or Dia to make a publication quality version.

Blank Baling: The Art and Value of Prototyping

One of the lectures that has stuck with me the most in my academic career was by Dr. Malloy about the value of prototyping. He would explain that archers, in order to practice their stance and release, would often stand blind-folded inches away from the target to practice shooting. By closing their eyes and focusing on their form, they learn to over come target anxiety. He analogized that prototyping software is very similar to blank-bailing. He described how by focusing on the smallest aspects of our system, we can try and learn by practice what design decisions do in the small scale without worrying how things will fit into a larger architecture. He encouraged us to create a “play” directory in our computer where we can feel free to try any odd thing and not have to worry about what it would do to the rest of our system or projects. Prototyping often and early has been one piece of advice has been one of the most transformative practices in becoming a software craftsman. In the remainder of this section, I want to highlight a few things about prototyping that I have learned since I started regularly practicing it a few years ago.

The first question that I had when I started prototyping regularly was what should I prototype? There are two cases in which I often create prototypes.

I often create a prototype for each new API that I want to use. Want to learn about MPI’s type system, make a prototype. Want to play with OpenMP tasking or nested parallelism, make a prototype. These prototypes were nothing spectacular, just enough code to do something useful or prove that something could work in a vacuum.

I also from time to time create prototypes of client and library code when I am creating a new interface. The goal with this kind of prototype is to determine what kind of information needs to pass across the interface boundary and how “ergonomic” an interface will be. By creating several examples of client code, I get a better idea of what will be efficient or easy to do and what will be a pain. It can also help me identify where I don’t have all of the information that I need, and I need to add an method to the interface.

The second major question that I face with prototyping is how can I avoid this code “ending up in production”? Prototype code often lacks important details (i.e. security, logging, documentation, and others) that would be in a “production-ready” code. So you often want to be careful about using it in a way that is likely to end up being used directly for someone else.

This is where the “play” directory comes into play. The “play” directory is not checked into the same source code repository that the “production code” would be. Additionally, I never share code in prototype form with others. If someone wants code that I have used for prototyping (it doesn’t happen often, but occasionally it does), I typically go through a short process of making it “production-ready” which involves adding a license file, commenting the interfaces, ensuring “secure” and “efficient” APIs have been used where appropriate, and adding some tests cases and assertions to ensure correctness. About 80% of my prototypes are fewer than 100 lines of code, with the average being about 61 lines of code including comments. The person you are giving the code will probably appreciate it the higher quality code and for 60 lines of code it shouldn’t take too long to make these changes.

Another major tool when building prototypes is mocks. Mocks are components that rather than interacting with a more complex aspect of your system, returns some predefined data. These can be really powerful in writing short code that can model some more complicated aspect of your system without bringing in the entire system as a dependency. Most languages have a library or two that make it easier to quickly build mocks from existing classes. Learning to use tools like these, can really cut down your time in writing prototypes

The last topic that I want to address here is when are higher level languages useful in prototyping? C++ is a fantastic language if what you want is the some of the absolute highest level of control about what code gets generated, but it isn’t always the best language for writing something quickly. Sometimes, you want the more robust library support, or don’t want to deal with questions like object lifetime. For cases such as these, I have found Python – and more recently Julia – to be great languages to prototype in. These languages come “batteries included” with language features that make writing quick and dirty code easy. However, some times what you want to prototype is how to do something specific in the language in which you are going to finally implement everything. In that case, you probably do want to use whatever lower-level language you will ultimately be using.

Focus on the interface: API Design Reviews

Another transformative talk that informed how I thought about software design was Titus Winter’s 2018 CppCon talk entitled “Modern C++ API Design”.

While this talk is focused on C++, it really got me thinking about what constitutes a good interface.

As I mentioned above, for anyone who has used Python is dict really the interface you want, or is it really a dict or is a Dict[str,int]? Or perhaps Dict[AnyStr, float] or even Dict[AnyStr, List[float]]

Likewise do you really want a dict or are you looking for something closer to a Java interface or a Rust trait?

Or does extension not matter, and what you really want is a struct with fixed names and types?

The interface you provide is essential.

It makes the difference between what is possible to achieve with a design and what is not.

So how can you ensure that you have the right design? Winter’s suggests, as others have, that there should be a design review for important interfaces to ensure they can be use efficiently and give the users what they need. Here are some questions that I think about when designing types:

- Is the usage of the class “intuitive”?

- Do I have to make several API calls to accomplish common tasks, or will a few calls suffice?

- Are there more than one way to solve a problem, and if so is it clear when to use each?

- Does each call do a minimal number meaningful of things?

- Does it fit within the larger software design?

- Does it use consistent conventions? Naming? Parameter ordering? Return values?

- Are their other existing classes with do similar things? If so why do both need to exist?

- Does the code use the same paradigms as the rest of the code?

- Does this design meet the functional and quality attributes goals of the architecture?

- What are the invariants that the class/function upholds? Some invariants I consider are:

- Ownership – who creates and then later who owns the object? Does it have static or dynamic lifetime?

- Uniqueness – how many copies of the object need to exist for its intended purpose?

- Constancy/Purity – what parameters are held constant vs. Mutable? How does it interact with its environment if at all?

- Thread Safety – what level of thread safety is provided?

- Exception/Error behavior – can the invariant be maintained in the case of errors/warnings?

- How well does this class/function follow the robustness principle (be liberal in what you accept, and conservative in what you return)?

- Am I really specifying the broadest interface that I can still consistently use correctly?

- You can find some my thoughts about liberal vs conservative interfaces here

- Does the function/class appropriately propagate errors at the correct level of abstraction?

Reviewing your plan after diagramming and prototyping some of the important APIs can really go along way into developing a use-able interface.

Good Requirements: Problems with Not Invented Here and Never Invent Here

As mentioned earlier, it is important to write good requirements. However, from my experience two of the most wrongly imposed requirements are that the code either be written by someone else (also called never invent here) or that it must be developed in house (so called not invented here). That is not to say that there isn’t a trade-off that must be weighed between the two, but it is seldom a hard requirement that must be carefully decided between. The reason I think these requirements are often over imposed is that they intuitively seem self-supporting.

Not invented here has been often driven by the engineering teams desire to create, the marketing teams desire to differentiate the product, or by the argument that “our case is different”. If you are the only user, and you are doing this to learn, the first can be a sufficient reason. However, the argument that your specific use-case is so different that you have to write everything or even most things from scratch is likely false. You may not be using the same words, you may not think about it the same way, you may have to change the default configuration or re-write modular component, but in all likelihood someone has done something very similar to what you are doing now.

Never invent here has often been driven either by the desire to reduce cost or effort. Components off the shelf (COTS) have many benefits, you don’t have to maintain them, you might not have to support them, and they likely are already finished. All of these properties are nice to have. However, if you never allow the possibility of building what you need, you may end up with an experience which is more generic than you might hope.

Ultimately, you have to weigh the trade-offs between these two cases and decide which more closely matches with what you are doing. Would writing this component provide sufficient value to overcome the additional maintenance and development costs?

So where can you find existing components? Today, there is a tremendous volume of code that has been open sourced. Provided it meets your license requirements and desired quality attributes, you can likely get it to work. However, you should also consider proprietary solutions.

Rational Expectations: Preparing for the Future versus YAGNI (You Ain’t Gonna Need It)

A similar conundrum that people get trapped in is preparing for the future vs YAGNI. This conundrum deals with how modifiable and modular should you make the code vs how simple the implementation should be. On one extreme you have “Enterprise Software” memes where any and everything can be reconfigured with a change to an XML file. On the other extreme you have code which is so tied to a specific implementation, you can’t change anything without re-writing from scratch. Over the years, I have been susceptible to both.

So how can you avoid the traps of either extreme? It really boils down to thinking carefully about what are rational expectations given your conversations with your stakeholders and your well-grounded beliefs about their future needs. It is crucial to ask not just might I use this in the future, but do I clearly foresee doing this soon? Additionally, it is important ask what will I have to change if I need to change this in the future, and how disruptive will that be? Between these two factors you can do a cost-benefit analysis as to which situation you find yourself.

Refactoring: Improving the Design of Existing Software

There is a reason the Martin Fowler’s signature book is the only book in this document to get its own subheading. This book really changed my expectations about what could be do quickly to change source code and my understanding about how it would effect users. You should definitely read it.

Two quick notes about refactoring. Since the development of Fowler’s book, a number of tool have been developed to preform basic refactoring. Which tools are best, and which tools work for which languages shift over time, but I strongly advise learning these tools. They take a lot of grunt work out of programming. In fact, I regularly use two different development environments for several languages because one of them provides better code writing/exploration facilities and the other provides better refactoring support.

The other key part of refactoring is how to quickly test if a change broke something. Of course if the code you are using has extensive unit-tests that have high coverage, you can just use that. If they do not, Approval tests can be a quick way to write tests for unfamiliar code. Essentially, they take an application and assert that the output hasn’t changed. Additionally there are a number of tools that can help you write Approval Tests quickly regardless of what language you use frequently.

Security and Threat Modeling: thinking about confidentiality, integrity, and availability,

It is often very hard to secure a system after it has been designed and widely deployed. Therefore you should think about the security of your system upfront. The process of planning for security often involves threat modeling. Consider each of the valuable or private aspects of data that your system may interact with. This can be personal information, expensive computing or storage resources, proprietary information, or a service that you provide. For each ask:

- Confidentiality: how can private information be inadvertently shared by someone without authorization? What would someone need to do to access this information?

- Integrity: how could private information be forged or modified without authorization? What would someone need to know to access this?

- Availability: How could private information be made inaccessible? What could someone do to prevent users or systems with appropriate access from accessing the information?

Now, just because there is a threat doesn’t mean that you will implement a mitigation. Some mitigation are prohibitively expensive to implement relative to their cost to remediate. Balancing these concerns is key to implementing a secure system.

- Consider the techniques (quality attributes, prototyping, diagramming, api reviews, rational expectations, refactoring, etc…) listed above to craft requirements into a design. Which ones have you used? How have they effected they ways that you design software?

What language/library should I use?

This is probably the question that several of you had when you first started reading this post. There is a reason that I waited until now to cover it: design is often more important than implementation. That doesn’t mean that you can’t have a bad implementation ruin a good design, but a bad design will ruin every implementation. The choice of language is an implementation detail that has trade-offs. In this sub-section, I present some things to think about when choosing languages.

First consider what existing work has been done. Are you starting on a “green-field” project where you are writing the first line of code, or are you adding to an existing code-base? Don’t just think about the code that you are going to be writing when you are making this decision. Think about code that you colleagues have or will write, think about what libraries and frameworks exist to do the task you are attempting. You don’t want to impose undue costs on yourself or your team by choosing something that no one else knows or uses for your task. That doesn’t mean that existing work should be dispositive (you eventually need to move on from Fortran-77 if only to a more modern version of Fortran), but it should weigh heavily on your decision.

You should also consider what language(s) you already know. Learning a language takes time. Is your goal to learn a new language, then great, ignore this advise. However, if your goal is to be productive, you may be better off sticking to what you already know.

You should also consider how the language will effect quality attributes. Two that are often important are stability and performance. Some languages are relatively young and need frequent changes to their syntax and standard library. They probably aren’t a good choice for a system that needs to last 10 years. Secondly, there is often a trade-off between compiled and interpreted languages in terms of runtime performance and development time. Consider carefully if machine time is more important than human time for your particular task.

So lastly, I want to close out this section with a brief table of what languages I generally recommend for which purposes:

| Purpose | Languages | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| New programmer | Python | Super easy to learn |

| New computer scientist | C++ | Exposes the how almost everything is written |

| “Enterprise Software” | Java | The language serves no other purpose in life |

| Containers | Go | Go produces tiny static binaries by default; great for containers |

| Interoperability | C/C++ | Almost everything has a C foreign function interface |

| Operating Systems | C | By the time you use only the features in C++ that work without an OS, you have C; Rust is getting close |

| Performance Critical | C/C++ | Nothing beats C/C++ for performance critical tasks |

| Prototyping | Python | Python is very concise, forgiving, and expressive |

| Safety Critical | Rust | Rust’s borrow checker and bounds checking are awesome tools for ensuring you have reliable behavior |

| Scientific | Julia, R, Python | Most code you commonly would write is already written for you |

| Web Back-end | Python, Go, Javascript | Javascript can also be used on the front-end, Go works well in containers, Python has great tooling |

| Web Front-end | HTML, CSS, Javascript | These are the standards, and you don’t have many other choices |

Implementation

Now that we have clearly thought about what design we want and which tools we are going to use, it comes time to finally implement the design In this section, I want talk about how to actually implement the software.

Learning A Language

Learning a specific language is out of scope for this article, but I recommend that you check out my posts on learning languages:

Tactics vs Strategy

The difference between tactics and strategy is the time-frame on which they play out. Strategy is the plan writ-large; tactics are the day to day, moment to moment decisions. Almost everything that I have talked about so far could be call strategy. Now I want to turn to focus on tactics.

Tactics are small units of change that you can introduce to your design to fix a particular problem. Here are some tactics we discussed in my course work:

- Any System

- Splitting – decompose a monolithic system or module into two or more modules; reducing cost of modifying a single responsibility.

- Substitution – one module is replaced by another with equivalent behavior but a different implementation

- Modular Systems

- Augmenting – an additional module is added to the system.

- Excluding – a module is removed from the system.

- Inversion – two or more modules are modified to create a third module that capture common behavior

- Porting – A module is divided into a into a module that is coupled to the system and another that is free from a single system.

- Layered Systems

- Maintain Semantic Coherence – ensure layers do make undue access to other layers

- Raise the Abstraction – create a new layer to encapsulate common work

- Abstract Common Services – group responsibilities within a layer into a service.

- Use Layered Encapsulation – layers either: + provide a facade to lower layers + provide an interface to the current layers new functionality

- Restrict Communication Paths – defines an ordering of layers such that layer N only access layer N-1

- Use an Intermediary – have one layer act on behalf of another layer

- Relax Layered System – allow a layer to access a deeper layer directly (for performance or simplicity)

- Layering through inheritance – a pattern that binds relationships between the layers at compile time

- Other tactics:

- General Encapsulation – putting a module behind an interface so that it can be replaced.

- Intermediary – introduce a module between two components to perform some extra work.

- Proxy – decouples the components of a system from being on the same system/process.

- Reflection – allow the system to inspect the state of services at run time to select an implementation

These aren’t the only tactics that exist. Martin Fowler’s book “Refactoring: Improving the Design of Existing Software” has a another large list of tactics that can be applied to a software system. They can be found his catalog of refactoring techniques online.

Lastly in addition to the question of what to do, there is the tactical question of what order to implement the system. In general you should start with the part of the system which provides the highest value at the lowest cost. However within that, there has been research on the ordering use to construct the various modules of a system (search for “Integration Test Order Strategies”). In general, these approaches create a dependency graph of the system then order the implementation of the software components in topological order of the resulting directed acyclic graph. They may have some weighting assigned based on the importance of the system, but that roughly the all work the same.

Comments

Nearly every programming language has a feature to include comments within the body of the source code. Additionally, tools like Git allow developers to associate comments with changes that they introduced to their source code. However, just because it is possible to comment, does not mean that a comment is the most appropriate way to communicate the message contained in the comment.

Comments are most appropriate when:

- The code would otherwise be completely opaque — for example most “lock free” using weakly consistent atomic featuring atom is or distributed synchronization code where the use of locks is distributed to several functions

- To document interfaces especially when it documents pre or post conditions that are not easy to express in code with functions like assert. For example that the code requires a pointer to be “registered” with some other call first, or that the function “frees” the memory associated with its input

- To provide macro level context of why code was written and what makes it different from other code that came before

- To mark TODOs for the code

- When the code serves as a personal reference or a teaching tool when it makes the code self-contained or to emphasize a subtle point.

I tend to favor a lighter comment style. A comment can be seen in some cases as a code smell indicating that the APIs and functions involved dose not reflect the intent of the code. A developer favoring this style of comments would use variable and function names to show intent rather than comments. Note that this works best when functions are small and describe a single intent.

Maybe that changes if the code is truly arcane (a regex, shell code, forth, awk, Perl, some Haskell for a C programmer, and TeX all come to mind) maybe this changes, and documentation is sparse to non-existent.

However it’s worth knowing in every windows IDE I have ever used you just hover unfamiliar APIs like VirtualAllocEX and the IDE summarizes either the call and it’s arguments. If your comment shows up on hover, you don’t need to add it.

I write comments while learning new APIs. I keep a running journal of code like this, and even have a directory on my machine for code like this called play (Thank you Dr. Malloy) for this code. It also has a place in teaching examples. When I was first learning Perl and Haskell, it annoyed me how terse some of the code was without any comments, and it was not until I found a book that had comments like this that I finally got it.

When thinking about whether and how to comment consider:

- Tools can do a lot for you (even tools like Vim), and you should think about if you are duplicating their effort.

- Good comments like code need to be updated and maintained with the code around them; is this comment worth the cost to maintain it in addition to the code?. Saying

closecloses a file in a comment is probably obvious and updating the comment is probably more effort than it’s worth, but I would not have guessed that VirtualAllocEx could allocate memory in another process. As a primarily a linux/unix developer, I appreciated this comment pointing out this huge possible foot-gun in the Windows API. - Git commit messages can not only serve as a place to keep important context about why a change was made, but also a high level summary of what is going on within a change. Reading through a large set of small changes is still challenging without some high level context of what was changed and why. In the note taking world this is called progressive summarization and is powerful in helping you review critical information quickly.

Tools

A key part of learning to be a software craftsman is learning how to make the most out of your tools. In is subsection, I discuss what kinds of tools to add to your belt and which ones that I use.

Text Editors

Another incredibly common question is what text editor/ IDE (integrated development environment) should I use? This is a highly personal choice which will differ from person to person. So while I don’t want to proscribe a particular editor, I do want to caution against what I see as two common foibles.

First, don’t shoot yourself in the foot by using a tool that provides so few features that you are going to be productive relative to more feature-full tools. In this category, I place editors like “pico”, “nano”, “gedit” on Linux, and tools like “notepad” on windows. These tools don’t provide useful features like auto-completion, auto-indentation, and in some cases even basics like syntax highlighting. There are many better tools that will help you write code better and faster. Use them, they don’t have that much higher of a learning curve.

My second – perhaps more controversial take – some IDEs are also not good choices. Some IDEs have high monetary cost, are tied to a particular language/tool-chain, and require you to learn a completely new interface for each language that you use. For these reasons, using proprietary IDEs may be not a good choice. That doesn’t mean that IDEs are not helpful, I use a proprietary IDE as a refactoring tool, but they shouldn’t be the primary tool in your tool-belt.

When you want these rich features, I would recommend instead using a tool like the Language Server Protocol.

The Language Server Protocol provides an API to many of the features commonly implemented by IDEs in a way that many text editors can use them.

This makes these features much more portable to different text editors if you ever need or want to switch.

Likewise, I also automate the things that Language Server does not with a small tool that I wrote called m

I’ve said quite a bit about what text editors what I wouldn’t use, so which ones do I recommend. I currently recommend:

- Vim – my daily driver

- emacs – another capable editor

- vscode – a light-weigh graphical editor

| Editor | Vim | Emacs | Visual Stdio Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pros |

|

|

Familiar Graphical Environment for new users while not pidgin holing you like an IDE |

| Cons |

|

|

|

| Common Misconception | Vim doesn't have advanced features like macros, autocompletion, syntax highlighting, code-formatting. In reality these features are hidden behind obscure keyboard shortcuts | Emacs key combos will hurt your hand. You can rebind almost any key, and plugin "EVIL mode" makes emacs much more ergonomic | You can't use VS Code on remote machines. In reality, it has built-in remote editing support that can edit files on other machines. |

| Getting Started |

vimtutor the build-in vim getting started exercise

|

|

Introductory videos on the help page |

| Next Steps |

|

|

Read the more extensive product documentatoin from the welcome screeen |

Debuggers

Debuggers are invaluable tools for programmers.

They allow you to step through a program at run time and interrogate the state of the program in a way that would otherwise be impossible or incredibly tedious.

Unfortunately debuggers are less universal than text editors.

I cannot just suggest one debugger that will work for every language even though gdb and lldb get close.

As such, I intend to point you to some features that are important and useful to have in your debugger.

- Run configurations/scripts – good debuggers allow you to allow you to save interesting sets of breakpoints/watchpoints and other settings in configuration files per project. You should use the features to be able to quickly run repeatable tests with your debugger.

- Core Dumps – While not as emphasized today, core dumps are a dump of memory from the execution of a process that is created when a process is killed by the operating system. It is designed in such as way that all the key state is contained within the core-dump file making them invaluable for debugging problems from users.

- Stop-hooks – stop hooks are a powerful feature when combined with break points. Stop hooks are arbitrary code that gets run when a breakpoint or watch point is triggered. You can use it to quickly print out useful state when the debugger stops or to make decisions about whether or not to a particular stop is interesting.

- Watch points and conditional breakpoints – Watchpoints allow you to pause execution when a particular region of memory is modified. Conditional breakpoints are breakpoints that only actually stop when some condition is true. Together, these tools give a lot of power to control when to stop execution.

- Writing plug-ins – Some of the most powerful debuggers like GDB and LLDB allow you to write extensions in a higher level language. They are several sets of the extensions that have been written and are used frequently such as

chiselandpwndbg.

Additionally, using a debugger is not a substitute for documenting and verifying your invariants (statements that are always true in your program) in your program.

Using language features or function like, C’s assert macro can save a lot of time of determining when your state has become invalid.

There is an argument to be made that assert shouldn’t be in production code; I’m ambivalent on the question.

On the one hand, yes invalid state is bad, but is a crash worse?

At the minimum, it is better when debugging your code; use asserts at testing time.

If you have to take them out during runtime, use a feature like C’s assert macro which remove debugs when the -DNDEBUG command line argument is passed.

Now some comments on how to use a debugger. As I have suggested elsewhere, debugging is a scientific exercise. You are creating a hypothesis that explains the behavior of the system, and you are using the debugger as tool to test that hypothesis. This has some implications for how you use a debugger. You aren’t going to just step through the program line by line. That is not a efficient use of your time, and it isn’t a efficient use of the debugger. Instead, postulate where you think the problem is, and stop there. If you don’t know where the problem is, use watchpoints or back tracing to find the suspect state. You’ll thank me later.

You can find more about GDB here.

Profilers

Profilers are typically “lightweight” tools that measure where the execution time of a program is being spent. They save you the effort of having to manually instrument your code at all points where you would like to gather timings. Some profilers can also incorporate low level system information from the kernel to give a more complete picture of performance.

One common problem across these tools is how to get a meaningful stack-traces.

Oftentimes, this comes down to two issues: including debugging symbols and not clobbering the frame pointer.

For gcc and clang with C/C++ programs, the flags you need are -g -fno-omit-frame-pointer, but there likely are similar flags for your language.

There are many different kinds of profilers. Each has its own advantages and disadvantages. Here are the ones that I use most often:

| Tool | Type | Usecase |

|---|---|---|

| Perf | sampling profiler | get instruction level usage information with low overhead |

| llvm-xray | call-sled profiler | get function call level overhead information with low overhead; Requires recompilation |

| callgrind | linker-based profiler | get function call level overhead information with moderate to high overhead; can simulate cache sizes |

| nvprof/nsight | Nvidia GPU profiling | You are profiling a GPU program on a Nvidia GPU |

| dtrace/ftrace/eBPF | Kernel call tracing | You want to profile time spent in the kernel |

You may also see suggesting to use gprof, In my opinion, this advise is largely out of date. The above tools are either higher performance, easier to use, or both.

Once you have a trace of the execution of your program, you will probably want to visualize it. There are a number of tools for this, the ones I use are:

| Tool | What it does |

|---|---|

| FlameGraphs | A set of Perl scripts that create SVG flame graphs which show hot spots in the application |

| KCacheGrind | An iterative tool that shows annotated call graphs |

Google Chrome’s chorme://tracing |

Interactive tool that can zoom in and out of complex and parallel traces |

To find more information, I would highly recommend Brandon Greg’s page on Linux introspection which lists a host of other tools to get the information you need during runtime.

Build Systems

Another key tool to become familiar with is your build system. Build systems as you expect allow you to build your project. Yes, you could write a shell script or a program to build your program, but a proper build system will do a better job than you can quickly do without it:

- parallelize your build according to dependencies

- handle caching and incremental compilation between builds

- download and include dependencies

- handle differences between compilers

- provide a system to cross compile for a different native architecture

- automatically provide hooks to customize installation, and debug builds

- provide reasonable defaults.

Every language seems to rely on its own build system and there are relatively few of them that work across languages.

So what should you learn to do with your build system? At the risk of being obvious, you should learn to automate your entire build process using your build system. This includes generating files when that is required, locating or downloading dependencies, or generating the source documentation. This may not seem like a big deal, but by integrating with a build system for your language, you often get a series of knock-on effects like tooling that can use the information provided by your build system.

Another key thing to automate with the build system is the deployment of your application, but more on that in a later section.

Why do this, it ultimately saves you time and effort for almost everything else you want to do.

Version control

Lastly, the final tool that you should learn is a version control system.

Without a version control system, you can still track changes yourself: You’ve probably had files on your computer called thing_v1.txt, thing_v2.txt, etc.

But then the question quickly becomes what if multiple team mates are making changes simultaneously, what was changed? Everything merged correctly? Why were things changed?

Version control systems solve the problems of

- tracking changes over time

- making it easier to understand why a change was made

- make it easier to share those changes consistently with others.

At this point in history, that tool used most often is git.

Git currently is prevalent because it scales well to extremely large code bases and is flexible enough to support a number of different work flows.

To learn Git, I recommend the git book

However, beyond the question of mechanics, there are questions of policy. When should you commit and why? If you commit, should you make one commit or a series of commits? What constitutes a good commit message? If you use branching, when do you use it and why? If you use branching, what will your strategy be around handling conflicts when code diverges? These are all questions that a seasoned craftsman should be able to answer.

So when should you commit?

There are two answers to this question.

On the one hand you should commit only when the code cleanly compiles and passes the test (a so-called atomic commit).

On the other hand, you might need multiple commits to have reasonable reversion points if you are making a big change.

So how do you resolve this conflict?

Different projects have different strategies, but I favor squashing the reasonable reversion points on development branches while avoiding rewriting history on the primary branch (typically called master or develop).

Other reasons to split commits would include to wall-off controversial changes from less controversial changes so they can be separately reviewed and committed.

Second, what constitutes a good commit message and why? Here is a post that I think thoughtfully addresses the issue. Ultimately it should be consistently formatted and spelled correctly, have a short descriptive title, a body that explains what was done, why it was done, and what other impacts it has, and cross references to issues databases if applicable.

Finally come the questions of branching. There are several different philosophies about this. There are naive answers like “don’t” but such answers don’t comprehend that in any distributed version control system, conflicts are inevitable on multi-person projects. More nuanced answers say things like, “one branch per feature”, “one branch per person”, or “one branch per release”. I’ve worked with each, and don’t have a strong opinion on which is correct. It is more important to be consistent.

Libraries

Also important to any development effort is what you won’t develop yourself. Libraries are a form of dependency that provide standard functionality that you can adopt into your code leaving these dependencies to others. While I talk about dependencies more fully in another post I wanted to briefly list here the more kinds of things that you typically want to bring in as dependencies, and some of the key trade-offs

Logging

Logging is a deceptively simple problem.

Yes, the absolute simplest approach of printing to stdout or console.log is really easy to do,

but very quickly, you have a much more complicated problem.

Here are some of the things that send people looking for more complex logging tools:

- automatic insertion of context (i.e. stack traces, hostname, time, etc…)

- distributed logging across several machines

- log immutability and tamper dectection

- filtering messages from a particular subsystem, severity, or host

- extremely high reliability requirements – if logging does not work, you can not debug anything

- extremely high bandwidth requirements – logging should not slow down the system

- extremely constrained resource requirements – for example

printkin the kernel needs to work before memory allocators are initialized. - human and machine readability

Appropriate logging frameworks differ for each language, but projects like open telemetry are trying to provide standard approaches to this that work across languages.

Configuration Files

Almost every program over a certain size has configuration files of some sort. When considering how to design your configuration files, the real question is what is your goal, and what will your users need and expect?

Here are some of the things that send people looking for more complex configuration tools:

- human readable error messages when an error is encountered parsing the file

- types other than strings

- fast parsing performance

- human and machine read-abilty

- machine and machine edit-ablity

Here are a few possible choices:

Languages like like CUE or dHall provide advanced features (data validation, schema definition and error reporting, code generation, scripting tools) but may not serve your particular language well or provide more features than you may need.

YAML is another popular choice, giving a lot of flexibility, but features aspects like type autodetection which are misfavored by some for the same reasons that implicit casts are disfavored by some in C++. Let’s be fair here: most the reasons people hate yaml are not yaml’s fault. They often boil down to the person who implemented yaml config files, essentially wrote a Turing complete programming language in them (cough Kubernetes), or to use it as a relational database and it is not the right tool for that.

TOML has many of the niceties of yaml but in my opinion provides less pain in the edge cases and stripping out some of the unneeded features.

JSON is ubiquitous and simple, but some would argue is really easy to typo. Classic ini files are also really simple, but lack schema validation.

XML is a very verbose (and often much maligned), but enables very sophisticated manipulation and expression which may be appropriate given the complexity of a particular use case – for example libVirt uses XML for virtual machine definition and the web uses HTML which is similar in several respects.

Several projects that use embedded python or lua as the config file language. This requires some setup, but is incredibly powerful granting functions, looping, variables, string manipulation, and object orientation. However all of this flexibility makes validation harder.

- What tools and libraries are part of your toolchain? If you do not use one of these tools why not? What would make your tool use more effective?

Testing

One of the most expensive aspects of software development is when software either doesn’t do what is supposed to. Even innocuous seeming changes can sometimes have massive unintented effects, being able to detect these quickly massively increases productivity. For this reason as soon as you know what you want to develop, testing code should follow swiftly after.

So now you have some code that is ready to test, how do you test it? Scholars divide testing into two categories: verification and validation.

- Verification - does the system do what the requirement says the system does?

- Validation - does the system do what we (the stakeholders) want it to?

As suggested earlier in the sections on diagramming and prototyping, verification and validation should occur at several points along the development process in order to ensure the software works as expected and to minimize development efforts. As such verification and validation occur in several forms. I don’t have room to say everything that could be said about testing.

You may be surprised that this section is far shorter than the others. On the one level, I’ve touched on verification and validation throughout the document. On the another level, writing good tests is just something that comes with practice In my opinion, writing good tests is one of the hardest skills to develop as a software craftsman. One the one level, its easy to write tests. You just do it using some library that makes it relatively easy for your language. On another level, ensuring that you have the right tests is far harder.

So what are the right tests?

Perhaps obviously, you should conduct sufficient tests to ensure that the requirements are obeyed for all inputs.

Does that mean you should test every integer between INT_MIN and INT_MAX? No.

But you should test enough of them to know that you didn’t make a mistake.

So how do you know what that is?

In practice, tests cases are chosen by:

- Choosing cases that execute a given function

- Choosing a few arbitrary cases

- Choosing boundary conditions (i.e.

INT_MIN, -1,0, 1, andINT_MAX, powers of 2 ± 1, etc for a routine that takes an integer) in addition to the arbitrary cases.

- Choosing cases that execute every branch of a given function at least once

- Choosing cases that execute every path through a given function

As you could imagine, as you go down the list the difficulty of creating the test cases becomes sizable, but we have more confidence that the implementation is correct. This has led to efforts to find ways to otherwise verify the correctness of an implementation.

Some more esoteric options that have been used to build a list of test cases before are:

- Use fuzz testing which uses random inputs for a given length of time.

- Use some generator which creates a provably sufficient set of test cases from the state machine that the program describes.

- Write two (or more) separate implementations that use different algorithms/designs and compare their answers for a number of inputs.

When you do your tests also matters. Tests can be ordered in terms of the amount of the system that they test. At one extreme, you have unit tests which test a single function or small set of functions. Slightly larger are integration tests which test interface boundaries between modules. Finally there are acceptance tests which validate the entire system (one example is approval test mentioned earlier).